|

Revised

6/25/2025 |

|||

|

|

The 34th Troop Carrier Squadron

|

||

|

War

Diaries |

|||

|

Following

are re-types of the Outline Histories and War Diaries sent up to Wing HQ each

month. The original documents are

preserved at the Air Force History Office at Maxwell AFB. AL, and have been

retyped for web format by Miles Hamby, son of Henry Hamby, original member of

the 315th TCS and first commander of the 310th TCS. The duty of writing the

war diaries at the time was usually assigned to the squadron adjutant and

typed by the squadron clerk. Often, as can be seen by reading these, the

writer was very expressive. The text herein has not been edited, but exactly

that that was submitted to Wing HQ and subsequently recorded in the Air Force

archives on microfilm. The type font used for these re-types is Courier to

provide similarity to the original font of the typewriters upon which the

diaries were originally typed. The formatting of text is not exact but

approximates the original document. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

HISTORICAL RECORD 34TH TROOP CAARRIER SQUADRON 1. Designation: 34th Transport Squadron, A. C. from 16th

February, 1942 to June 30th, 1942. Redesignated: 34th Troop Carrier Squadron from 1st Muly, 1942. 2. Organization: Activated 17th February, 1942, at Olmsted

Field, Middletown, Pa. per Par. #11, General Order #1, Hr. 315th Troop

Carrier Group, at Olmsted Field, Middletown, Pa., dated 17th February, 1942. 3. Cadre: A cadre of three

officer and thirty-two enlisted men of the 6th Transport Squadron were

assigned t the 34th Transport Squadron per S.O. #1,

Hq., 315th Transport Grouo,

Olmsted Field, Middletown, Pa., dated 17th February, 1942. ORIGINAL CADRE 1ST Lt. John Lacy 2nd Lt. Henry G. Hamby, Jr. 2nd Lt. Otto H. Peterson M/Sgt. Barnes, Robert E. Thomas, Cpl.

Jeffie W. T/Sgt. Ricks, William. Cpl. Cipolla,

john f. S/Sgt. Gusky, Joseph, Cpl.

Brown, Morris S/Sgt. Lalonde, Cpl. Wilbur E.,

Cpl. Aye, Ernest Sgt. Mclain, John E. , Cpl.

Brennen, Edmond Sgt. Shields, John H., Cpl. Grassmic,

Solomon O. Sgt. Ferko, Andrew J, Cpl. Puwalowski Sgt. Phillips, Stanley,, Pfc.

Rogers James R. Sgt. Usoff, George E , Pfc.

Kornfeld, Samuel Sgt. Kanner, Kenneth K, Pfc.

Wilkinson, Donald S. Sgt. Poretti, John E, Pfc. Hicks, Harry Sgt. Brown, James H, Pvt. Gill, harry A Sgt. Vrenna,Robert, Pvt.

Schultz, John Cpl. Davis, James D, Pvt. Anstell,

Donald Cpl. Andrewlavage, Stanley E, Pvt.

Baker, Joseph, D Cpl. Jacoby, Pvt.

Minor, Edward Later filler: Forty-three officers and

202 enlisted men were assigned to the squadron from July to October, 1942

before departing for the ETO. The

enlisted men assigned to the squadron were arriving day and night at all

hours. They came singly, in two’s, and in large groups. They were in all

stages of training from recruits of a few days of army life to well trained veterans. The Army Air Force specialist

schools contributed the greatest number of our enlisted personnel. The radio

operator's, and majority, came from Scott Field, Illinois. Our airplane

mechanics came from a number of schools throughout the country. Some of the

schools they attended were Chanute Field, Illinois; Academy of Aeronautics,

La Guardia Field, New York City and Keesler Field, Mississippi. Practically

all of the parachute riggers attended to school at Chanute Field, Illinois.

Some of the squadron clerks were graduates of the school at Ft. Logan,

Colorado; but the most of them had received all of their clerical training at

their civilian jobs. The balance of our men were

assigned to us from the Reception Training Center, Bowman Feld, Kentucky. The majority of our commissioned pilots

were assigned to the squadron during August and September, 1942. Almost half

of these pilots received their advanced flying training at Lake Charles,

Louisiana; and the other half were trained at Columbus, Georgia. The officer

who later was to become our Commanding Officer, May 17, 1942, Donald G. Dekin had his training at Kelly Field, Texas. During the month of August, 1942; we were

assigned enlisted pilots. The majority of these pilots received their

advanced training at Luke Field, Phoenix, Arizona. The rest of the enlisted

pilots were trained at Kelly Field, Texas. Our navigators were assigned to us during

the months of August and September, 1942. Eleven of these navigators were

assigned to the squadron after they returned to the United States after

having taken the 60th Troop Carrier Group to England via the North Atlantic

route. The navigators had their training at various schools, namely;

Pan-American Airways; Coral Gables, Florida; Turner Field, Albany, Georgia;

and Mathers Field, Sacramento, California. One administrative officer was assigned

to the squadron during July, 1942. The remaining fillers were assigned during

August, September and October. The administrative officers were largely

graduates of OCS and OTS, Miami Beach School, Miami Beach Florida. On the 18 of August, 1943; twelve

enlisted Liaison Pilots were assigned to the squadron from the Combat Crew

School, CCRC No. 11, APO 634. A little over a month

later (22 September, 1943), they were transferred to the 153rd Liaison

Squadron, 67th Reconnaissance Group, USAAF Station 471 per S.O. 257 HQ., VIII

Air Support Command. On the 22nd of September, 1942;

twenty-nine Glider Pilots were assigned to the squadron from the 12th

Replacement Control Depot. They consisted of one 1st Lt., four 2nd Lt., and

twenty-four flight officers. The majority of Glider pilots took their

Advanced Flying Training at Lubbock, Texas, in Dalhart, Texas. Prior to

coming overseas, these Glider Pilots took a vigorous course in Commando

tactics at Bowman Field, Kentucky as part of their training for overseas

duty. During May, 1943; a complete crew flew

the Atlantic by the southern route and were assigned to the squadron as a

crew. During August, 1943; a complete crew and several parts of crews were

assigned to the squadron after crossing the Atlantic on the northern route.

Some of the crew members crossed as passengers only. 4. Resume of Movements: Squadron

departed Olmsted Field, Middletown, Pa., at 1900 hours 17 June, 1942. Arrived at

Bowman Field, Kentucky, 1530 hours 18 June, 1942 and departed at 1030 hours 3

August, 1942. Arrived at

Florence Army Air Base, Florence, South Carolina at 1930 4th August, 1942. AIR ECHELON:

(36 officers and 91 enlisted men) Departed

Florence Army Air Base, Florence, S. C., at 1315 hours 11 October, 1942. Arrived at

Kellogg Field, Battle Creek, Michigan at 1705 hours 11 October, 1942 and

departed 1000 hours 28 October, 1942. Arrived at

Presque Isle, Maine at 1330 hours 28 October, 1942 and eight airplanes

departed at 1045 hours 7 November, 1942. Three airplanes departed at 1045

hours on the 17th November, 1942. Arrived at

Goose Bay, Labrador 1345 hours 7 November, 1942 and departed 0930 hours 8

November, 1942. Arrived at

Bluie West 1, Greenland 1600 hours 8 November, 1942

and departed 0800 hours 8 December comma 1942. Arrived at

Rejkavik, Iceland 1430 hours 8 December, 1942 and

departed 0900 hours 12 December, 1942. Arrived at

Prestwick, Scotland 1130 hours 12 December, 1942. GROUND ECHELON:

(8 officers and 134 enlisted men) Squadron

departed Florence Army Air Base, Florence, S.C., at 2000 hours 16 October,

1942. Arrived at

Fort Dix, New Jersey 2300 hours 17 October, 1942 and departed 2100 hours 23

October, 1942. Arrived at

New York Port of Embarkation at 2330 hours 23 November, 1942 and departed

0700 hours 24 November, 1942. Arrived at

Scotland 1500 hours 29 November, 1942 and disembarked at Greenock, Scotland

1130 hours 30 November, 1942. 1. Organization a.

This organization has always been a part of the

315th Transport Gorup or the 315th Troop Carrier

Group. b.

Before leaving the United Sates, the squadron was

a unit of he I Troop Carrier Command and the 52nd Troop Carrier Wing. C. Upon arrival in the E.T.O.,

the squadron became a unit within the VIII Air Force and the VIII Air Support

Command,. d.

On the 30 August, 1943, the squadron became

part of the 1st Fighter Division (Prov.) within the VIII Air Support Command. e.

On the 16 October, 1943; the squadron came

part of the Ninth Air Force and IX Troop Carrier Command. (G.O. #3, IX, T.C.C., 16 Oct., 43) The following Tables of Organization have been in effect for this

squadron since its activation: Table of Organization #1-317 1

July, 1942 Change

#1, 4 September, 1942 Change

#2, 25th January, 1942 Table of Organization #1-317 3

February, 1943 Change

#1, 28 May, 1943 Change

#2, 28 June, 1943 Table of Organization #1-317 16

August, 1943 Change

#1, 23 October, 1943 2. Strength as of 30 November,

1943 Ground Echelon – 20 Officers – 25 Flight Officer – 184. Air Echelon Assigned - 48 Officers – 14

Flight Officers – 57 EM – 1 W/O Assigned

- 21 Officers - 3 Flight Officers – 75 Enlisted Men. 3. Date of arrival at and

departure from stations occupied in the ETO. GROUND ECHELON Arrived Aldermaston, Berkshire,

England (SSAAF Statin G-467) 1400 hours 1 December, 1942 and departed 1230 hours 25 May, 1943 to Blida, North

Africa. Arrived Welford Park, Berkshire, England, *USAAF) Station G474) 110

hours 6 November, 1943 AIR ECHELON Arrived Aldermaston,, Berkshire, England, USAAF Station G-467) 1400

hours 12 December, 1942, and departed 1230 hours 25 May, 1943 to Blida North

Africa. Arrived at Blida, Algeria, 1430 hours 29 May 1943 4. Losses in action – Negative 5. Awards and Decorations The Air Medal for meritorious achievement was awarded to the

following: 1st Lt. William L. Brinson – Pilot F/ O Charles D. Wilson –

Co-Pilot 1sr Lt. Roger E. Chapman – Navigator T/Sgt. Morris Brown - Crew

Chief S/Sgt. Robert E. Eiden - Radio Operator (then Sgt.) NARRATIVE Out of this World War II, Air Power has proven itself a mighty weapon

for the destruction of the enemy's war industries and shipping facilities.

True, the Troop Carrier Units do not do that type of work, but the work

outlined for the Troop Carrier Unit is just as important as the work of the

bomber or fighter squadrons. Transport planes are carriers of the vital

weapons of war. They carry supplies, personnel, mail, airplane parts, and

other necessities. What once would require days or even weeks to transport

vital supplies to the fighting men at the front lines,

now requires a few hours or even minutes. From the United States to the far

outpost of the world, transport planes are delivering men and material to the

fighting fronts. As one of these implements of war, 334th Transport Squadron had its

birth at Middletown Air Depot, Middletown, Pa. on February 17, 1942 -- a unit

of the 315th Transport Group. Like all the Air Depot stations, Middletown required transport planes

to carry supplies to the many air fields all over the country. This was the

role played by the 34th Transport Squadron--carrying freight and passengers.

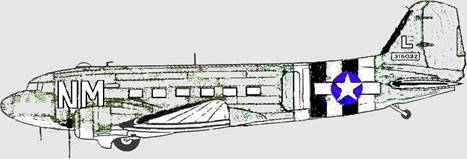

The planes were Douglas C-47’s and C-53’s borrowed from the Second and Sixth

Transport Squadrons. The many missions carried the planes and crews

throughout the United States as well as to the Caribbean (Cuba, Puerto Rico,

Trinidad)and to Goose Bay, Labrador. On May 17, 1942, Lieutenant Donald G. Dekin

was placed in command of the 34th Transport Squadron relieving Lieutenant

John Lacey who was transferred to the 35th Transport Squadron. Lt Dekin’s home is at Ilion, New York. He attended Pratt

Institute, having been graduated from that institution in 1933, after

studying Industrial Chemical Engineering. His army experience began in March,

1939, when called as a flying cadet. In March, 1940, he was commissioned a

Second Lieutenant. He married Miss June Farmer on 16 June, 1940, about three

months after he received his commission. He has two children, Donald George Dekin, Jr., and Timothy James Dekin.

At that tie, all transport pilots were required to

fly 1,000 hours as a co-pilot before given a first pilot's

classification. At the time of Lt. Dekin's appointment as Commanding Officer, he had flown

1,450 hours in DC-3’s which was a well earned

appointment. On the 18 June, 1942, the Squadron was transferred to Bowman Field,

Louisville, Kentucky. Here, the Squadron received orders to build from a

cadre to full strength. The Squadron performed routine duties in anticipation

of building to wartime strength. On 1 July, 1942, the Squadron was redesignated the 34th Troop Carrier Squadron, a name that

classified it better in regard to the type of work it was to perform. The 34th Troop Carrier Squadron was transferred to Florence Army Air

Base, Florence, South Carolina, on 3 August, 1942. At that time, the Squadron

Commander held the rank of Captain. During the next three and one-half

months, the Squadron was built to nearly complete strength in preparation for

overseas duty. New pilots arrived and were trained for transport flying.

Eleven navigators arrived, after having taken the Sixtieth Troop Carrier

Group to England over the North Atlantic route. Eleven airplanes were

assigned to the squadron. The personnel were completely equipped for field

conditions. The flying personnel were organized as combat crews and flights

A, B, and C were formed. After months of preparations for overseas duty, the squadron was

ordered to begin movement to the ETO. On 11 October, 1942, The Air Echelon

moved in mass formation on the first leg of their trip to cross the Atlantic.

Flights A, B, and C arrived at Battle Creek, Michigan, for final

preparations. Immediately after their arrival, the entire Squadron was

restricted to the base for security reasons. An intensified training program

began for the entire combat crews. Over water flights were made, briefing

sessions were given on the air routes to follow, and the Air Echlon was completely outfitted for their air movement Having completed the training at Battle Creek, Michigan; the Air Echelon

moved to the final “jumping off” place in the United States. They arrived at

Presque Isle, Maine on the 28 October, 1942. Having made all necessary

preparations, there was nothing more to do but wait for favorable weather

conditions. Eight of the Squadron airplanes departed 7 November, 1942,

staying overnight at Goose Bay, Labrador, and then traveling onto Bluie West, Greenland. The other three airplanes departed

Presque Isle on 17 November, 1942. Since the weather was a great factor in

the air movement, there was considerable delay at each leg of the flight. The

longest delay was at Greenland. This was the last massed air movement over

the northern route that fall. The hazards soon to be encountered warranted

great daring and skill of flying if the squadron were

to reach its destination safely. While the squadron was awaiting favorable weather in Greenland, they

performed several search missions for the rescue of airplane crews that were

forced down on the ice caps. Temperatures were recorded at 50 degrees below

zero, winds of 100 miles velocity, and ice caps of 12,000 feet in height. All

of these dangers, added to the treacherous downdrafts and long hours of

flight (sometimes 6 to 7 hours of duration), was sure proof as to the

alertness of the crews and their efficiency. Most of the Squadron spent at

least thirty-five days and when not flying, there was little to do except to

read or to play card games. Captain Donald G. Dekin

received the rank of Major in November 1942. After thirty-five days of waiting for favorable weather, the day

finally came. The Air Echelon departed for Rejkavik,

Iceland, on 8 December, 1942. Civilization was a welcome site for the crews

after Greenland's bleakness. The Air Echelon's final leg of the route brought

them to Stornaway, New Hebrides, Scotland, and then

to Prestwick Scotland, on 12 December, 1942.

From there on down to the new base, (Aldermaston, Birkshire,

England), was only a matter of few hours flight. The Ground Echelon departed from Florence, South Carolina, for the

Fort Dix Staging Area via train on 17 October, 1942. As there they were to

await the overseas journey, restrictive measures were put in force

immediately and they were kept constantly on the alert for two weeks. An

intensive training program was formulated. The training program

included medical lectures, physical training, close in order drill,

training films, school of the soldier, and varied lectures on army technicalities.

After fourteen days of restriction, the ban was lifted to give all personnel

living within a radius of 100 miles of Fort Dix, New Jersey, an opportunity

to visit their homes before departing for overseas duty. The squadron Ground Echelon departed Fort Dix, New Jersey, for the New

York Port of Embarkation on 23 November, 1942, and boarded the HMS “Queen

Elizabeth”, at 2300 hours the same day. The ship steamed out of New York

harbor at 0700 hours the 24 November, 1942. Most of the men, even though tired,

were on deck to see the Statue of Liberty wave bon voyage to them. After six

days at sea, the Ground Echelon arrived at Greenock, Scotland, on 30

November, 1942. The morning of the following day, the personnel disembarked

and boarded a train for the new base. After fourteen hours of traveling on

the one train, the squadron Ground Echelon arrived at Aldermaston, Berkshire,

England. All personnel were happy to find that their journey was over and

that they would be settled for a time. They were given the task of house

cleaning in anticipation of the Air Echelon who were

still on the way over. The 34th Troop Carrier Squadron along with the group was assigned to

the VIII Air Support Command of the Eighth Air Force. The Group took over

command of Aldermaston, Airdrome and operated as a base function. A large

number of the Squadron personnel acquired additional station duties. The combat crews were immediately placed on detached service with the

VIII Air Support Command. They operated from Hendon Airdrome, London; Burton

Wood Airdrome, North Wales; Langford Lodge Airdrome, North Ireland. From

these several fields, the task of carrying freight, passengers, and mail for

the entire United Kingdom began.

Operating as the only Troop Carrier Group in the United Kingdom, the

Group was known as the “workhorse” of the Eighth Air Force. They were also of

service to the Royal Air Force. During hazardous flying conditions such as

bad weather, instrument flying weather, difficulty of dead reckoning due to

the many airdromes, ballon barrages, etc.; the

combat crews show the highest skill. The crews were highly praised by the

eighth air force officials. There were no major airplane accidents during the

entire period. This type of work occupied the Squadron for 5 months. Occasionally

the crews were given relief to return to Aldermaston for a rest period. Most

of the Navigators saw more service than the other members of the crews. At the Aldermaston Airdrome, the officers held dances every Saturday

night and the enlisted men held dances every two weeks. Moving pictures were

held at first twice a week and finally as service got better, they were held

nearly every night. Members of the squadron made many friends among the

civilian population of the air. A few members met their one and only and

after receiving the required permission, they married. Passes and leaves were

frequent and gave personnel ample opportunity for seeing the Country. The

moral of the Squadron was very high. Several of the navigators were loaned to ferry groups for the purpose

of navigating flights of fighter aircraft to the North African theater of

operations. They traveled in bombers as the ”mother

ship” for the movement. The following named personnel of the 34th Troop Carrier Squadron; 1st.

Lt. William L. Vincent, pilot; 1st. Lt. Roger E. Chapman (then 2nd Lt),

Navigator; F/O Charles D. Wilson, co-pilot; T/Sgt. Morris Brown, Crew Chief;

and S/Sgt. Robert E. Eiden (then Sgt.), Radio

Operator, received the Air Medal for meritorious achievement in flying to

North Africa. They were carrying high-ranking observers of the USAAF and RAF.

The airplane was flown unarmed over enemy held territory and was continuously

subject to enemy fire. The successful. Completion of the mission reflects the highest credit upon the mentioned

personnel. The flight was made in March 1943. Authority for award of the Air

Medal to the above named officers and enlisted men (General Order #179,

Section II, Headquarters, Eighth Air Force, dated 7 October 1943). A course in commando training was given for the officers and in

enlisted men. It covered a two week period and consisted of intensive

physical training set up on the pattern of the British Commando School. There

were two of these courses given. There were other courses offered various personnel,

such as; intelligence, chemical warfare, engineering, booby traps, and

various army field training. In preparing for the group movement to North Africa, a training

program was formulated in May 1943 which consisted of glider towing, dropping

of airborne infantry, night formation flying, and night cross country

missions. The program lasted for two weeks, and drew to a conclusion with the

inspection of the combat crews by the Commanding General of the Eighth Air

Support Command. After having been restricted to the field for several days following

the training program, the group along with the Squadron was loaned by the

Eighth Air Force for approximately six weeks to the Twelfth Air Force

presumably for the invasion of Sicily. For the second time, the squadron was broken up into Air Echelon and Ground

Echelon. The Air Ashland departed Aldermaston Airdrome on 25 May, 1943, for

North Africa, arriving at Blida, Algeria, on the 29 May, 1943. The Ground Echelon remained at Aldermaston Airdrome and continued to

operate the base. At that time, no compliment squadron was on the field. As

the weeks rolled by, the air Echelon did not return as was expected; so

everyone felt it would be a long while before we would see them again. On 30 June 1943 come the squatter Ground Echelon participated in a

station parade, marking the transfer of Aldermaston Airdrome from the R AF to

the USA.A f. The RAF flag was lowered and the Stars and Stripes took its place. Air

Commodore C. E. V. Porter represented the RAF and Colonel R. L. Maughan

represented the United States Army Air Force. In October 1943; four of the new crews of the squadron had an escape

exercise in cooperation with the civilian police. The crews were loaded on a

truck, bindfolded, and dumped off out ten miles from

our camp at Aldermaston, Berkshire, England. They were dumped in crews as

though they were paratroop. Their problem was to evade capture by the

civilian police and find their way back to camp before dark. The civilian. Police were alerted but did not start their search until half an hour

after the crews were dumped out The evaders were authorized to “borrow”

military vehicles and one officer had a little trouble. He had taken a

reconnaissance car in Newbury and had driven out of town the wrong direction.

Upon retracing his route, he was stopped for stealing the car. After a few

phone calls between the military police and our S-2 office, he was finally

cleared of the charge. Quite a few vehicles were taken but all of the

“temporary thieves” were caught. The “evaders” had a great deal of trouble

trying to locate where they were as the road signs were few and far between.

The first two, of the four that got back safely, arrived within six hours.

They had well-earned the pot of several pounds Sterling contributed by the

men as a prize for the first one to return safely. The exercise was complete success. A great deal was learned and it

created a great deal of interest and enthusiasm among the crews for s 2

information. On the 18th of October 1943 come 5 officers and 15 enlisted men were

transferred out of the Squadron assigned to Headquarters, IX Troop Carrier

Command as part of the cadre for this new command. One of the officers who was transferred to HQ, IX Troop Carrier Command was

appointed to Squadron Commander of Headquarters and Headquarters Squadron, IX

Troop Carrier Command. He is 1st Karl L. Kirshner

(now Captain Kirshner), pilot. On the 6th November 1943; the Ground Echelon departed from USAAF

station G-467 Aldermaston, Berkshire, England and arrived at USAAF Station

G-474, Welford Park, Berkshire, England, the same day. This was a permanent

change of station. The duties performed at the new base were similar to those

performed at Aldermaston commonly general based duties and details. While at

Welford park calm hour refueling unit operators refueled all airplanes of the

434th Troop Carrier Group, who were at Welford park on maneuvers. Our

Commanding Officer, Major Donald G. Dekin, was

promoted to the temporary rank of Lieutenant Colonel effective the 13

November, 1943. As soon as the Squadron, Air Echelon arrived at Blida Airdrome,

Algeria, the Squadron relieved the 64th Troop Carrier Group of all transport

duties. The Squadron then proceeded to operate as they did in the United

Kingdom by carrying freight, mail, and passengers to all quarters of the

theater. The records of freight mail and passengers for September 1943 to

October 23, 1943 as follows: Passengers

9,735 Miles flown 217048 Pounds of

freight 781,763 Hours flown 1635 Pounds of mail 550,795. By the above record one can plainly see that the squadron was doing

quite a bit of flying. /// |

|||

|

(Below) Facsimile of original report

dated 5 July 43 by Maj. Stark, 34th TCS, regarding operations for Month of

June 43 while 34th TSS was detached from Aldermaston. Maj. Stark would become first commanding

officer of the 309th TCS formed in May 1944 in anticipation of the Normandy

invasion. |

|||

|

HEADQUARTERS, AIR ECHELON 315TH TROOP CARRIER GROUP Office of the Operation Officer (APO #786 – U S Army 5 July 1943 SUBJECT: Accomplishment Report

for Month of June. TO : Commanding Officer, 315th Troop Carrier

Group. 1. The following report on the accomplishment

of the 315th Troop Carrier Group for the month of June 1943 is submitted for

you information: PERIOD No. PASS Lbs. FREIGHT Lbs. MAIL MILES FLOWN HH FLOWN June 1 – June 1372 157,793 NOT INIATIVE AT THIS TIME June 6 – June 12 5596 461,330 98,601 155,028 1135 June 13 – June 19 5821 591,635 157,753 133,099 987 June 20 – June 26 4299 543,417 135,389 117,401 850 June 27 – June 30 2717 306,330 75,101 70,595 519 TOTAL 19805 2,060,505 466,834 476,163 3,491 2. The information for the

above report is taken from the “Pilots Missions Report” which is turned into

Operation upon completion of each trip. 3. The number of passengers, pounds of

freight, and pounds of mail hauled are considered as “pay load” and does not

take into considerations the number of stops where the same person, freight,

or mail may have been counted or weighed again before departure on the next

leg of the trop. 4. Definite information on the percentage of

airplanes in commission during the month of June not complete. The percentage of lanes in commission will

be submitted in the report for the month of July. SMYLIE

G. STARK Major,

Air Corps, OPERATIONS

OFFICER. DISTRIBTUION 1

C.O.

315th T.C. Gp. 1

C.O.

34th T.C. Sq 1

C.O.

43rd T.C. Sq 1 File |

|||

|

(Below) Facsimile of

original report from Col Hamish McLelland to 8th Air Support Command Group HQ

at Aldermaston regarding temporary assignment to North Africa for month of

July 1943. |

|||

|

HEADQUARTERS, AIR ECHELON 315TH TROOP CARRIER GROUP Office of the Group Commander APO # 768 – U. S. Army 18 July 1943 SUBJECT: Temporary Duty in North Africa To: :

Commanding General, VIII Air Support Command, APO 618, U.S. Army, (Attention Chief of Staff). 1. The 315th Troop Carrier Group prepared

twenty-one (21) airplanes for temporary duty in North Africa in accordance

with letter 452.1 x 320.2 your Headquarters, dated 14 May 1943,”loan of Troop

Carrier Flight Echelons and Airplanes.” The airplanes were to be completely

modified for operational use and the engine times to be less than 400 hours.

Only the air Echelon was to accompany these planes with a few extra pilots

and no spare parts. The movement ordered dated 23 May 1943 stated that the destinations was Relizane

Algeria reporting to the Commanding Officer, 51st Troop Carrier wing for

temporary duty of approximately six weeks. 2. The group departed the United Kingdom the

evening of 27 May 1943 arriving Casablanca the morning of 28 May 1943. The

destination was changed by a telephone message sending the flight to Oujda,

Algeria. The flight arrived Oujda at noon 29 May 1943 where written orders

were issued for the group to proceed to Blida, Algeria to replace the 63th Troop

Carrier Group on the Courier and Freight Service in North Africa, being under

the control of the 51st Troop Carrier Wing for administration and Northwest

African Air Service Command for operations. 3.

The 64th Troop Carrier Group was ordered to move from Blida to Nouvion where they were to begin training with paratroops

and gliders for operational missions. The 315th Troop Carrier Group replaced

squadron by squadron the 65th Troop Carrier Group on the Courier and Freight

Schedule in North Africa. While this replacement was in progress, the 51st

Troop Carrier Wing transferred either (8) of the original twenty-one (21)

planes to other Troop Carrier Groups for operational use as they were

completely modified. In order that the 315th could replace the 64th,

thirty-nine (39) old planes were transferred, to the Group from the 60th,

62nd, and 64th Troop Carrier Groups, bringing our total fifty-two (52)

planes. Additional crews were placed on temporary duty, with this Group

making a total of fifty-two (52) crews. The old planes transferred to the

Group were short of necessary equipment; engines in very poor condition, many

requiring engine changes; as they had been in operation in the desert for

several months under the most unfavorable condition. 4.

Group Mission. a. Twenty0six (26) airplanes assigned to

thi3 34th troop carrier Squadron were responsible for the passenger courier

flight witch were made in accordance with the attached schedule. Sixteen (16)

planes and crews were necessary each day to fulfill the schedule, taking

passengers, mail and urgent air freight to and from twenty bases in North

Africa extending from Agadir, French morocco to Tripoli. Special mission

other than scheduled flight, are made when extra aircraft were available in

the Squadron. An average of 90 hours was flown by the 34th crews during the

month of June. The group was temporarily assigned to the Mediterranean Air

Transport Service by the enclosed order, who inaugurated a new schedule

requiring twelve planes, each flight ten to twelve hours a day and twenty crews

each day with each flight five to six hours. b. Twenty-six (26) airplanes assigned to the

43rd Troop Carrier Squadron receive the Priority Freight Mission for A-3

Northwest African Service Command each evening sending all available planes

to haul freight to and from any place urgently needed. These Planes cover all

the territory in North African theater, Malt, Gozo

Island, Pantalleria shortly after its capture and

into Sicily seventy-two hours after the invasion. Supplies and equipment were

hauled to the Tunis Area and litter patients would be brought back to

Algiers. The average time of the crew during the month of June was 90 hours. c.

One plane was schedule three evening a week to drop, British Chinese,

and a American

paratroop from 1930 to 2130 hours.

This gave the plane crews valuable training. d.

Attached is a Group Accomplishment Report for the month of June 5. A

total of 88 maintenance men were attached to the Group from other Troop

Carrier Groups making a total of 135 men, including the crew chiefs both with

the air Echelon to perform all the maintenance of fifty-two planes. Since 10 June 1943, fifty (50) engines have

been changed, four (4) are being changed at the present time, and none are awaiting to be changed. During the first two weeks in

June, fifteen (15) tires blew out, and being unable to obtain new ones from

the depots, tires had to be taken from planes Grounded at the home station

for other reasons and placed on the planes needing tires. An average of

sixty-five (65) 100 hour inspections are being pulled per month in addition

to the fifty and twenty-five hour inspections and other work. Our maintenance

men and crew chiefs have been working from six o’clock each morning until

nine o’clock each night. Their morale and high efficiency of work are to be

commended. No engine accessories are available and to old ones must be used

on the new engines; generator control panels must be

repaired while the airplanes are Grounded a s new ones are not available.

Engine stand or dollies could not be obtained at the depots. Flare pistols,

flares and Aldis Lamps were not available for the

protection of our crews and planes. 6.

When the 64th Troop Carrier Group departed Blida, it left the 315th

responsible for all Americans on the base and all base functions. Difficulty

was encountered in seducing a telephone switch board and telephones until

finally they were secure directly from the SOPSS without going through the

usual channels. A request was made for transportation and at the present time

have on 2000 gal gas truck eight two and on half (21/2)ton

trucks, two ambulances and two cleatracs. A

requisition for a mimeograph machine and stencils was made at the depot two

weeks ago but they are not available. With the responsibility of the base, very

few of the TBA items including Air Corps equipment have been available.

Cooks, KPs guards, telephone operators, drivers, teletype operators,

parachute rigger, painters and carpenters have been supplied from the small

number of 64th enlisted men left at Blida on temporary service at the time of

their departure. 7. Difficulty was encountered by S-2 in

securing colors of the day, verification codes and syko

cards. The group was transferred so often that it was never on any commands

distribution list. 8. On

1 July 1943, this Group was relieved from attachment to the Troop Carrier

Command and attached tot the Northwest African Air

Service Command for administration and to the Mediterranean Air Transport

Service, Mediterranean Air command, for operational duty, 9.

Although the Group did not participate in the mission which it was

apparently to North African to do, it relieve on group (64th Troop Carrier Grop) from duty on the Courier Service so that they could

take part in the invasion of Sicily. The six weeks temporary duty as ordered

expired 12 July 1943.

/a/ HAMISH McLELLAND

/T/ HAMISH McLELLAND

Colonel, Air Corps, Commanding |

|||

|

|

|||

|

WAR DIARY 1 December 1943 To 31 December 1943 |

|||

|

2 December 1943 |

Once aircraft with crew dispatched to Wool

fox Lodge, Lincolnshire for the purpose of transporting personnel. |

||

|

4 December 1943 |

Detachment “A” – Lt. Moore, an attached

pilot while on a routine flight across the Mediterranean, sighted and

aircraft in the water and upon investigation found five or six persons in the

water nearby in life vests. He circled low and dropped a liage[SIC] raft and notified a nearby

and notified a nearby hospital ship and the R.A.F. Coastal Air Force station

at Tunis. Lt. Col. H. B. Lyon returned

from England brining 44 sacks of mail for the detachment. Nearly everyone was

up until after midnight reading mail. |

||

|

6 December 1943 |

Major William L. Parker, 0-353026, Group

S-1, was appointed Group Administrative Inspector as an additional duty. |

||

|

9 December 1943 |

One aircraft with crew was dispatched to Bovington, Hertfordshire, and thence to Raydon, Suffolk on detached service for ten days. Two

enlisted men transferred from headquarters of the Group to Headquarters, IX

Troop Carrier Command. |

||

|

12 December 1943 |

Detachment “A” – Bad weather, and hence no

flights. Preparations are being started for the return of the Detachment to

England early in January. |

||

|

13 December 1943 |

Detachment “A” – Some flights cancelled,

others forced to return to base account of weather. |

||

|

14 December 1943 |

Detachment “A” – Weather clearing up and

all flights departed on schedule; some were forced to return. Temporary crews

were set up for the forthcoming trip to England and the decisions made to

carry no passengers on the trip. |

||

|

17 December 1943 |

Several promotions in Group Headquarters

today as follows: Appointed Technical Sergeant (Temporary) S/Sgt. GEORGE P. OSWALD, 12044953 (542) Appointed Corporal (Temporary) Pfc. FRANK C. BAKER, Jr., 39407763 (807) Pfc. DORRIS C. GORHAM, 35090182 (239) Pfc. JACK (NMI) STEIN, 32439623 (501) Pfc. KENNETH H. WAGGONER, 32251573 (501) |

||

|

18 December 1943 |

Appointed Private First Class (Temp) Pvt. George, N. doll, 37432880 (501) Pvt. NNOEL R. SEIM, 16050412 (501) Pvt. EARL (NMI) THOMAS, 33234416 (501) |

||

|

19 December 1943 |

F/O George L. Peavey, AC, of the 34th

Troop Carrier Squadron was, in addition to his other duties, was appointed

Asst. Group Intelligence Officer. |

||

|

20 December 1943 |

Pfc. Guy W. Tustin, 33088478, was promoted to

Corporal (Temp.) Detachment “A” – preparations for departure to England are

now in full swing. Air craft to be used on the trip are Grounded and cabin

fuel tanks being installed. |

||

|

21 December 1943 |

Pfc. Irving (NMI) Cohen, 12142702, was

promoted to Corporal (Temp). Detachment “A” – Activity increases. Aircraft

being modified completely for the return to the United Kingdom. The 34th

Squadron is to take 11 planes; the 43rd is to take 10 planes. Day

otherwise normal. |

||

|

22 December 1943 |

Detachment “A” –Activity as usual but with

a minimum amount of runs due to Grounding of the 21 aircraft. |

||

|

25 December 1943 |

Detachment “A” – Christmas day, and very

little activity, all departments either being closed down or operating with skeleton

staffs. A very good Turdy dinner was served and the U.S.O. show furnished

very good entertainment in the evening. |

||

|

26 December 1943 |

In addition to his other duties, 1st

Lt. Bartley D. Rienhardt, 0-339348, AC, as detailed

as Group Personal Equipment Officer. |

||

|

27 December 1943 |

Six aircraft and crews were dispatched to Bottesford, Nottinghamshire on a non-operational mission. |

||

|

28 December 1943 |

Detachment “A” – attached personnel who have

worked in the various departments are taking over those departments to

relieve the Detachment for the tri back to the United Kingdom. |

||

|

31 December 1943 |

Detachment “A” – Several liaison pilots

attached to the Detachment have received orders and left today to return to

the United States. /// |

||

|

|

|||

|

Historical Data 34th Troop Carrier Squadron 1 January 1944 to 31 January 1944 NARRATIVE The new year

brought with it high hopes of uniting the Ground Echelon and the Air Echelon;

but on the 11 January, 1944, official word was received postponing the Air Echelon

movement to the United Kingdom for another three months. The Air Echelon then

resumed operation as in the past. The Air Echelon statistic record for the

period of 2 January, 1944 to 29 January, 1944 is as follows: Number

of Passengers Carried 4,698 Pounds

of Freight 376,015 Pounds

of Mail 32,773 Miles

Flown 184,694 Hours

Flown 1,402 Meanwhile,

in the United Kingdom, the Ground Echelon were still

holding classes in Chemical Warfare and Mines and Booby Traps. The Ground Echelon

also, as in the past since the Air Echelon departed, carried on Squadron and

Station duties. The flying

personnel which were still in England were getting

in their flying time by flying Piper Cubs local and a few cross country runs

in the transport. A large number of them were kept very busy on Ground jobs

of the Squadron, Group and Station. A few of the crews got to fly a couple of

days on maneuvers with the 434th Troop Carrier Group. On 26 January,

1944, another escape exercise was held. All the glider pilots and the power

pilots which hadn't been on the last exercise participated. They were the

parachutists and as such were blindfolded, hauled in trucks to various points,

ten miles from camp at Wilford Park, Berkshire, England. The civilian police

were again the main searchers. A large number got back without being tagged

than on the previous exercise. Twenty-two of the fifty-three participants of

the group returned safely. The first participant to return safely was F/O.

Emilio A. Garza of the 43rd Troop Carrier Squadron. He had received rides and

was in within three hours of the dropping time. The exercise was much easier

for the evaders than previously due to the constant flow of military traffic

on the roads and a large number of road signs. Both traffic and road signs

were few and far between a few months ago. Upon return to the station, the

S-2 personnel conducted individual interrogations to give crews and personnel

practice in reporting “flash reports” and general military information. WAR DIARY JANUARY, 1944 1. One crew of the Air Echelon went on a Secret cross

country trip today. 2. Three crews of the Air Echelon went on a Secret

cross country trip. 3. Five crews of the Air Echelon returned from a cross

country trip. Pfc. Hannah of

the Ground Echelon was sent to, RAF Code and Cypher's School, No. 5. 4. Four crews of the Air Echelon went on a secret cross

country trip. Cpl. Carens, Thomas J., of the Ground Echelon was assigned and

joined the Squadron today. He is a

classification special. 5. Two crews of the Air Echelon left on a secret cross

country trip today. 6. Three crews of the Air Echelon return today from a

secret cross country trip. Cpl. Lewis Salek of the Ground Echelon, duty [sic due to] to AWOL

and later admitted to the Station Sick Quarters with injuries sustained in an

accident. 7. Nineteen enlisted men were attached to the Air Echelon

today. Five crews of

the Air Echelon returned from secret cross country trips. 8. Four enlisted men were relieved of assignment to the

Squadron Air Echelon and then attached to the Squadron Air Echelon for duty,

quarters and rations. For crews of

the Air Echelon returned from cross country trips and three more crews went

on a cross country trip. 9. Five crews of the Air Echelon returned from a cross

country trip and four crews went on a cross country trip. Cpl. Samuel M

Brooks and Pfc. Charles S. Klug were sent to the Command Defense School at

USAAF STATION 489. S/Sgt. George M. Armstrong was sent to VHF Rad Main School

at USAAF station G-476. Cpl. Lewis Salek was

reduced to the grade of private with prejudice. These four men are all in the

Squadron Ground Echelon. 10. Three crews of the Air Echelon returned from cross

country trips and four crews went on a cross country. 1st. Lt. G.

E. Dawson, Ground Echelon returned from RAF Anti-gas School, Salisbury, Wilt,

England. 11. Word was received today canceling our Air Echelon's

return trip to the United Kingdom for another three months yet. Both the officer’s and enlisted men of the Air Echelon were highly

disappointed, for they were looking forward to a return trip to England. Three crews

of the Air Echelon returned from a cross country trip and two crews went on a

cross country trip. 12. Three crews of the Air Echelon returned from cross

country trips and two crews went on a cross country trip. Five enlisted

men of the Ground Echelon were sent to the USAAF Station 467 to repack the

parachutes belonging to the Squadron. 13. Five crews of the Air Echelon returned today from

cross country trips. 14. Three crews of the air Echelon returned today ad

lone crew went on a cross country trip. Five glider

mechanics in the Ground Echelon were transferred in grade to the 434th Troop

Carrier Group. Five glider

mechanics and three airplane mechanics of the Ground Echelon were transferred

in grade to the 435th Troop Carrier Group. 15. Five crews of the air Echelon return to the base

from a cross country trip. Sgt. George M

Armstrong of the Ground Echelon returned to the squadron from VHF Radio Maintenance

School. 16. To crews of the Air Echelon returned from a cross

country trip and three crews went on a cross country trip. The five enlisted

men of the Ground Echelon who were on detached service at USAAF STATION G-467,

repacking parachutes, returned to the squadron. Captain West and 1st. Lt. Dawson, AMS-AC

(Temp.) were promoted to Captain and 1st. Lt., respectively in the, AUS

(Temp.)effective, 1 January, 1944. 17. Three crews of the Air Echelon returned from cross

country trips and three crews went on a cross country. 2nd Lt. Fry, was promoted to

the rank of 1st. Lt, (Temp.) AUS-40. 18. Four crews of the Air Echelon returned from cross

country trips and two crews went on a cross country trip. 19. Three crews of the air Echelon returned from cross

country trips and three crews went on a cross country trip. 20. Three crews of the Air Echelon returned from a

cross country trip and four crews went on a Secret cross country trip. Cpl. Dante A.

Mancini of the Ground Echelon was transferred in grade to Detachment of Patients

302nd Sta. Hosp. Cpl. Brooks

and Pfc. kluge returned from Command Defense School, the above named

personnel were in the Ground Echelon. 21. Three crews of the Air Echelon returned from a

cross country trip and three crews went on a cross country trip. Cpl. Samuel Brooks

was sent on detached service to the Command Defense School, to help teach the

course. 22. To crews of the Air Echelon returned from a cross

country trip and four crews went on a cross country trip. 23. Three crews of the Air Echelon returned from a

cross country trip and five crews went on a cross country trip. 24. Three crews of the air Echelon returned from a

cross country trip and three crews went on a cross country trip. Pvt. Joe

Bernie was transferred in grade to Det. of Patients and Gen. Hosp. 25. Five crews

Of the air Echelon returned from a cross country trip and three crews went on

a cross country trip. Promotions came through for 14 enlisted

men (3-Cpls to Sgts., 8 Pfc. to Cpls,

and 8 Pvts. to Pfc.) these were in the Ground Echelon.

26. A prisoner of war escape experiment was made by

sixty officers of the squadron and interrogation of officers who participated

in the exercise. To crews of

the air Echelon returned from a cross country trip ,

and three crews went on a cross country trail. Pfc. kluge

was sent to Killkeel, Ireland for the purpose of

attending the AA Machine Gun School. 27. Four crews of the Air Echelon returned from a cross

country trip and three crews went on a cross country trip. 28. Three crews of the air Echelon returned from a

cross country trip and three crews went out on a cross country trip. 29. One Second Lieutenant attached to this organization

was transferred to the Personnel Center No. 1 for trans-shipment to the United

States. Two crews of the air Echelon

returned from a cross country trip and four crews went out on a cross country

trip. 30. Five crews of the Air Echelon returned from a cross

country trip and three crews went out on a cross country. Cpl. Orlo G. Haman (truck-driver), was

transferred in grade to Headquarters Squadron, 315th Troop Carrier Group. 31. To crews of the Air Echelon returned from a cross

country trip and four crews went on a cross country. /// |

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

(315th Group Headquarters) WAR DIARY 1 February 1944 To 29 February 1944 |

|||

|

1 Feb 1944 |

A Flying Evaluation

Board was appointed (SO #16, 1 Feb 1944) for the purpose of evaluating the

professional proficiency of personnel who hold currently effective

aeronautical ratings. The Board

consisted of: Capt. Maurice L. Malins O-386203 MC 1st Lt. Edward F. Connelly o-790520 AC 1st Lt. Donald S. McBride O-669757 AC |

||

|

3 Feb 1944 |

The following men

of Group Headquarters were awarded |

||

|

|

|||

|

Mar 44 |

|||

|

|

|||

|

Apr 44 |

|||

|

|

|||

|

HISTORICAL

NARRATIVE 34th

TROOP CARRIER SQUADRON 1 MAY

1944 TO 31 MAY 1944 NARRATIVE Military training, if it is to be either

interesting or effective.be relevant to the struggle and tactical problems it

purports to help solve. The relevancy should be clearly demonstrated, and in

any case must be clearly understood. If there were a common denominator, a

key note in the month’s training, it might be summed up in one word,

relevancy. The interest and enthusiasm exhibited by Squadron pilots,

aircrews, and even Ground personnel, reflected faithfully two things: a

growing appreciation of the magnitude and difficulty of the imminent project,

and a training problem well-designed to fit a troop carrier unit for its

particular task in the coming invasion of Adolph Hitler’s festering Europe. Despite intransigent stretches of mind,

thick cloud and rain, many days in days in May found the Squadron’s Skytrains flying in three huddled elements of three in

skies of comparatively unbroken blue. Squadron aircraft flew close formation

with the Group in twenty separate exercises each averaging two hours. On four

other occasions, the Squadron participated in paratroop-drop maneuvers. On

the 24th, dummies were released very accurately in the Drop-zone. The

paratroops practice mission on the 11th was a failure in that the aircraft

were unable to locate the drop-zone. The airborne troops were not released.

They returned safely to the field via c-47s. Of these four missions, all but

one were successful, and all but one, the “dummy

drop”, were flight maneuvers. Several flights were scheduled during which the

Squadron aircraft were to tow gliders and a demonstration of the glider

pick-up procedure was made. Inclement weather frequently interfered. Three

flights of [?} two to five aircraft each, towed gliders during the month. Ground school session featured much varied

but important subjects as first-aid, the treatments of secondary shock,

ditching procedure, aircraft recognition, “glider snatch” technique, escape

and evasion, air-sea rescue and its relation with communications procedures,

paratroop tactics, and the current situation on the battle fronts. All

aircrews attended. The Squadrons glider pilots attended a

three-day course of instruction in the organization of airborne infantry, the

mission of airborne troops, the duties of glider pilots completion of a

glider mission, hand-to-hand combat, mines, booby traps, demolition, infantry

weapons and their use, concealment and camouflage, fox-holes and gun

emplacements. They participated in field exercises in establishing command

posts and outguards, and patrolling and scouting. In the communications department, the

veteran and the student operators were hard at work learning W/T [walkie/talkie] procedure, installing

tow-ropes for glider and tow-plane inter-communication, studying radio

operations procedure and radio navigation aids, and installing crystals for

“A” and “D” channels in the Squadron aircraft. These radio operators acquired

valuable operational experience in that they accompanied every flight and

maintained contact with air-Ground training stations. In addition to training, there was a great

deal of administrative activity during the month. The long awaited orders and

numbers arrived, for activation of two of our squadrons in the Group. The

“split up” of our squadrons to form a cadre for one of the new squadrons was

accomplished. Tis schism and the Change of Table of Organization a few days

later greatly relieved the promotion situation. Many deserving men could be promoted. The

problem remained of who was the most deserving. During the month, twenty-one C-37As were

transferred out of the Squadron and the Squadron acquired two new C-47As. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

WAR DIARY (1

May 1944 to 31 MAY 1944) 1. The Squadron continued its training program by

flying a twelve-plane formation with the other Squadron. From 1430 – 1630,

three aircraft towed gliders. In the evening the Squadron flew over three

hours. The pilots showed considerable interest and improvement in formation

flying. Five enlisted glider mechanics were

attached to the Squadron for maintenance of Squadron gliders. Fifteen radio

operators flew over two hours and communication with the air-Ground stations. 2. Ground school convened from 0800 to 1030

during which period the letter from General Spaats

pertaining to Air Force accomplishments was read. This was followed by a

lecture on first aid. Twelve Squadron aircraft flew in the group

formation for three hours in the morning and five aircraft towed gliders for

an hour and a half in the afternoon. Ten Squadron radio operators flew two

hours n the afternoon and communicated with air-Ground

training stations. Eighteen men practiced one hour each on W/T. Nine radio

operators worked half a day preparing tow ropes for inter-communication between

glider and tow-planes. The flying schedule for the evening was

cancelled because of the winds. One major, two captains, eight 1st

Lieutenants, seven 2nd Lieutenants, sixteen flight officers and fifty-eight

enlisted men were transferred to the 310th Troop Carrier Squadron to form the

latter’s original cadre. 3. Glider towing, scheduled for the morning,

and all other types of flying were cancelled because of high winds and

inclement weather. “Ditching Procedure” was the subject

discussed in Ground school; all combat crews

attendees. Ten radio operators worked on tow-ropes

for inter-communication between gliders and two-lanes and practiced for one

hour on W/T. 4. The Squadron’s glider pilots began a

three-hour course of instruction on

the organization of airborne infantry, the mission of airborne troops, the

duties of glider pilots upon completion of a mission, hand-to-hand combat,

mines, booby traps, demolition, emplacement, practical in establishing

command posts, outposts, outguards, and, also, patrolling.

The instructors were three officers and one enlisted from an airborne

regiment, veterans of two Mediterranean campaigns. The regular morning Ground school featured

training film on navigation. Twelve Squadron aircraft flew with the Group

formation for one and a half hours during the afternoon; and twelve aircraft

flew during the evening. Twelve radio operators communicated with

air-Ground training stations during the day’s flying. Eleven men practiced

for one hour on W/T. Three enlisted glider mechanics were

attached to the Squadron. One

new aircraft, type C-47A, was assigned to the Squadron. 5. There was no day flying, but during the

evening, ??? aircraft flew

from 1830 to 2030. New crystals were installed for the “A”

channel; the ??? brush up

on their ???; ???????

which would participate in the evening’s maneuver. Briefing was conducting in the pilot’s

lounge in the afternoon. Weather was ideal and the aircraft were loaded at

1830 for a 1930 takeoff. Our Group was designated the lead group over the

drop-zone. The lead ship arrived over the DZ at 2100, the specified hour, and

the release of paratroops was completed in 10 minutes. This proved to be a

very successful mission. Thirteen radio operators practiced for

two-hours on W/T, and eighteen radio operators attended a lecture on aircraft

radio operating procedures for two hours. Fourteen radio operators flew with

the evening’s mission and communicated with air-Ground stations. 7. The Ground school consisted of a critique on

the previous night’s paratroop drop, and the paratroopers stated that they

had been dropped closer to the DZ than they had at any previous drop. The critique lasted two hours. In the afternoon and evening, the Squadron

continued for hour on W/T and then attended a one hour lecture on radio

operating procedure. 8. Another paratroop maneuver was conducted

today along lines similar to the previous night’s exercise. The afternoon briefing was held in the

pilot’s lounge. Takeoff was at 2230 hours. The Squadron flew three elements of three

ships each. The DZ was reached at 0030

and all but three ships of the Squadron dropped their paratroops. These three aircraft encountered a strange

flight of C-47s, took evasive action, and were unable to get back on course

for the drop. All aircraft of the

Squadron not actually engaged in the night’s paratroop maneuver towed gliders

from 1330 to 1630. Rebecca equipment in two aircraft had been

discovered to be out of order and repairs were initiated. Six newly assigned radio operators received

practical instruction on procedure and operation from experienced radio

operators. Sixteen radio operators

practiced for one hour on W/T and the six new men, later in the afternoon,

attended a two-hour lecture on the operation of the aircraft radio sets. Thirteen radio operators flew with the

evening’s paratroop mission and communicated with air-Ground training

stations. One officer and eight enlisted men were

assigned, and two officers, on flight officer, and five enlisted men were

transferred. 9. In the afternoon, nine Squadron aircraft

flew in the Group formation, after which the Squadron’s flying officers

attended a meeting. Seven radio operators practiced W/T for

one hour. Six radio operators attended a lecture on the operation of aircraft

radio sets. Seventeen C-47A’s were transferred to the

310th T.C. Sqdn, and four C-47A’s were transferred

to the 316th T. C. Group. 10. In the afternoon, nine Squadron aircraft flew

in the Group formation. One glider tow-rope was fitted for

tow-plane to glider to inter-communications.

Eighteen radio operators flew during the afternoon and communicated

with air-Ground training stations.

Seven trained radio operators flew with experienced radio operators

for procedures experience and instruction.

Eighteen men attended class on radio navigation aids in the United

Kingdom and eighteen radio operators practiced W/T for an hour. 11. A third paratroop drop was scheduled for this

day. It was to be the largest, planned

paradrop in which the Troop Carrier Groups over the

U.K have participated. The paratroop

unit xxxx and Airborne Division. Xxxx at 1700 hours with the aircrews. The aircraft took

off at 0x00 hours and reached the DZ at 0800 hours. None one of the airborne

infantry was dropped because of excess altitude and had inability to find the

DZ. Two aircraft which did not participate in the maneuver towed gliders in

the afternoon. IFF on one of the aircraft was out-of-order

and was repaired. Thirteen radio operators practiced W/T for one and half

hours, and thirteen radio operators attended a lecture on radio navigation

aids. Seven other radio operators attended a two-hour lecture course on radio

equipment operation. 12. A critique was conducted in the afternoon

covering the previous night’s operation. Polices were established re: the

Group formation and methods of dropping. The flying schedule today was cancelled

because of poor visibility. Noe crystals were installed for “C”

channel in all Squadron aircraft. Eight radio operators worked this afternoon

on tow-ropes for inter-communication between tow-planes and gliders. 13. Both day and night flying were cancelled

because of poor visibility. Eighteen men attended instruction for one

hour in “Q” code class, and eighteen men attended a one hour class on W/T.

Later in the day, eighteen radio operators attended a lecture on night flying

navigational aids and navigational aids in the United Kingdom. One radar officer and four enlisted men

were assigned to the Squadron. 14. It was a fine day. In the afternoon there was squadron

formation flying. IN the evening,

twelve aircraft flew cross country in formation for 2½ hours. Glider flying that had been scheduled for

the morning was cancelled. Eighteen radio operators flew for 2½ hours

in the afternoon and communicated with air-Ground training stations. Eighteen

men attended a one hour class in “Q” code. 15. For three hours n

the afternoon, the Squadron planes flew with the Group formation. Eighteen radio operators flew with

formation and communicated with air-Ground training stations. A surprise party was given in honor of

Col. McLelland, the Group commanding Officer.

And although many of the Squadron officers had received no advance

notice of the event, most of them arrived and thoroughly enjoyed the

affair. Enthusiasm was at the highest

during s contest, the winner or which was to receive the second piece of the

birthday cake. A newly organized

station band provided the music for listening and dancing. Everyone seemed to enjoy themselves. 16. On the afternoon’s training agenda was film xxxx operations xxx on the British desert campaign, taken

as a sign that movement of the Squadron was anticipated for the following

day; all passes were cancelled. There was no flying today. Eighteen

radio operators attended a course on night flying navigational aids and radio

navigational aids in the United Kingdom. 2nd Lt. Newly [?} and 1st Lt. {?} [illegible] 17. [entire text undiscernible] 18. The Squadron flew for one hour and fifteen

minutes n the afternoon. Sixteen radio operators flew with the

afternoon formation and communicated with the air-Ground training

stations. Seventeen radio operators

practiced W/T for one hour. 19. All combat crews attended a class in aircraft

recognition. Following this, the Group intelligence officers gave a lecture

on the week’s news and changes in the battle fronts. Inclement weather prevented flying today. Fifteen radio operators practiced W/T for

one hour, and fifteen radio operators attended class for “Q” code for one

hour. One officer was transferred to the 53rd T.

T. Wing and three enlisted men were assigned. 21. The pilots indulged in local formation flying

in the afternoon. High flying was

scheduled for the evening, but weather closed in and flying had to be

cancelled. Two radio operators flew one hour this

morning and communicated with air-Ground training stations. Two 1st lieutenants, one 2nd lieutenant,

and two flight officers were assigned to the Squadron; three 2nd lieutenants

(navigators) were transferred to the 310th T.C. Sgdn.

22. Group headquarters panned another paratroop

exercise, but unfavorable weather prevented the execution of this plan. Four

Squadron planes flew a radar flight for two hours. Six radio operators flew this morning and

communicated with air-Ground training stations. Fourteen radio operators

practiced W/T. 23. The paratroop drop scheduled for the evening

was again cancelled because of inclement weather. There was no other flying

during the day. Fifteen radio operators practiced W/T.

fourteen radio operators attended a lecture on navigational aids in the

United Kingdom. 24. Twelve Squadron aircraft flew for two hours and

forty-five minutes in the afternoon for a practice “dummy para-drop”

exercise. All the aircraft arrived at

the DZ in a reasonable interval, and a greater percentage of the “dummies”

hit the dropping zone, too. Fifteen radio operators flew with the Squadron

and communicated with air=Ground training stations. Eighteen radio operators

practiced W/T, and twelve radio operators attend a lecture on navigational

aids in the United Kingdom. 25. All combat crews and glider crews [rest is

undiscernible] 26. [text is undiscernible] 27. In the afternoon, twelve Squadron aircraft

flew with the Group formation for two hours and forty-five minutes. The radio operators who flew with mission

communicated with air-Ground training stations. 28. Twelve Squadron aircraft flew cross-country

with the Group formation for two hours n the

afternoon. All radio operators who flew today

communicated with air-Ground training stations. We were assigned one new aircraft, type

C-47A. One officer was assigned to the Squadron. 29. IN the afternoon, twelve Squadron aircraft

flew with the formation. Twelve aircraft were scheduled for a flight in the

evening, but this schedule was cancelled because of inclement weather. The Squadron intelligence officer lectured

to combat crews on escape and evasion. One enlisted man was assigned to the

Squadron. 30. All combat crews attended a class on aircraft

recognition and training films of the dropping of paratroops. Twelve Squadron aircraft flew with the

Group formation for one hour. Three enlisted men were assigned to the

Squadron. 31. All combat crews participated in one hour of

athletics in the morning and attended a lecture in first aid. Five Squadron aircraft towed gliders in

the morning, and twelve Squadron aircraft flew with the Group formation for

one hour in the afternoon. Flying

scheduled for the evening was cancelled because of bad weather. This afternoon was pay-day for both

officers and enlisted men assigned to the Squadron. Eight officers and eight enlisted

men were assigned to the Squadron. Fifteen radio

operators attended a lecture on map-reading and principle of navigation. Perhaps the least tasteful but the most

broadly practiced maneuver in this month’s training schedule was a lesson in

mobility. On the 17th, the Squadron

simulated a mass evacuation --- officers and enlisted men packed their

personal and aircraft were loaded with full crews and equipment. It was all done in orderly fashion, and the

inspecting officers credited the maneuver as being largely successful. Had the vent been recorded in Motion

pictures, a ghostly montage might have lingered on the film --- a specimen of

General Brereton’s many widely dispersed signs: “Keep Mobile”. Even in the category of troop carriers, it

is neither an army’s job is its fate to stay in one place. /// |

|||

|

|

|||

|

HISTORICAL

DATA 34th TROOP

CARRIER SQUADRON 1 June

1944 through 30 June 1944 Almost from the very first minute, there was a newness, a strangeness in the air an expectancy and,

still, a restraint. Some personnel, perhaps with psychic sensitivities,

suspected much; but, their but their suspicions went unvoiced. Unnoticed were

the tell-tale rust-colored rolls of barbed wire that had grown up among the

weeds and effectually separated those who know too much from those who knew

nothing at all. Over everything was a superficial gloss of normalcy. Ground

school consisted of lectures on escape and evasion, ditching demonstrations,

first-aid, and summaries of the current war news. Combat crews participated

from time to time in athletics. The drone of motors was sporadic in the sky

but just enough to seem usual and casual. On the first, one squadron aircraft

flew locally for thirty minutes; on the second, one aircraft made a Rebecca

test flight while another flew cross-country; on the third, a Pathfinder crew

accomplished a cross-country mission. More paratroopers had arrived – big,

tough specimens of manhood---and were interned within the rust-colored barbed

wire enclosures. It aroused little comment. For many weeks this had been

"S.0.P." in the disposal of paratroopers---the barbed wire seemed

to be more for our own protection than for anything else. On the 3rd of June, the communications arteries of from

Carrier Command leading to subordinate units were suddenly glutted with

secret instructions. With equal suddenness a heavy restriction descended upon

the base. Officers appeared at the gates to augment the regular guard

strength. Vehicles passed neither in nor out unless on official business of

an urgent nature and properly conveyed by an "escort" officer:

Passes for both enlisted men and officers were cancelled. The lights in Group

intelligence and operations offices gloved all night. And yet, there was a phenomenal

lack of rumor. Those discerning enough to see in this activity something of

unusual importance were intelligent enough not to talk about it. The less

discerning were awakened by cloud-filtered daylight on June 4th at the

scheduled time; saw two Squadron Sky-trains take the air on cross-country

flights and return two and one-half hours later; or were silently thankful

that the cancellation of Ground school for that morning had added,

incrementally, to "sack-time". By noon, a field order had been disseminated

to certain staff officers of Group Headquarters; normal business was in a

state of strange suspense. Weather was, inconveniently, miserable, By the morning of the 5th, twelve Squadron aircraft

were on the line and ready for loading. Squadron intelligence and operations

officers had been informed of the nature of the impending operation. They

gathered the appropriate maps, charts, and photographs for briefing in the

afternoon. At 1500 hours, pilots and navigators, arrayed in full field

equipment---flak suits, helmets, pistols, gas masks, impregnated

clothing---filed into the Squadron intelligence office. There they received

their escape purses, kits, and more cheerful items such as gum drops, chewing

gum, soap, and cigarettes. Their faces were sober. In the space of a few

hours, youths had changed into men. In the pilot's lounge, they were

thoroughly briefed by Lt. Col. Robert J. Gibbons, the Group Operations

Officer. Among the ranking officers present was Major General Ridgway of the

82nd Airborne Division. They proceeded, then, to their own “leper

colony", to be cut off from the outside world until the mission was

accomplished. At 1700 hours, the remaining members of the combat crews,

already equipped, filed into a briefing room. Lt. Giles E. Dawson and Lt.

John R. Kirk, squadron intelligence Officers, were present to conduct the

briefing. “This is where you are going this evening." Lt.

Dawson's voice was quiet, his phrasing studied. A hush fell on the roam as he

produced a specially-prepared map of the northern coast of France. His finger

traced a path leading out over the English Channel, skirting the isles of

Guernsey and Jersey, bending northeastward to cross, the Cherbourg peninsula.

"The paratroops will be dropped here, on Cherbourg Peninsula, at a

crossroads immediately southwest of the village, St. Mere Eglise.” He indicated a point on the map. “You will

cross the peninsula, fly out a few miles-over the Channel to the northeast,

and then follow the reciprocal of the route in. If you should be So

unfortunate as to find yourself on the Ground, you can expect our soldiers to

the northeast of where you land.” Lt.

Dawson reminded the crews of certain basic principles of escape and evasion,

and the briefing was over in a quarter of an hour. Lt. Kirk took the crews to the mess hall,

escorted a few to latrines, and finally, deposited them in the Base Chapel to

await further instructions. From 2000 hours to 2100 hours, a few trucks ran along

the perimeter track, halted occasionally and moved on. Their drivers had been

instructed to carry certain equipment to certain hard-standings. It was the

sort of thing that happens every day at any aerodrome. In the chapel, the interned the interned

crews could hear motors revved up, a few at a time, sustained for several

minutes, and then cut off. They

realized it was a most important warn-up. To other base personnel, it wars

the normal noise of normal operations. A few minutes before 2100 hours,

trucks drove up to chapel, stopped in the street. Crews piled aboard. The

convoy rolled, trickled onto the field, scattered, made brief stops at

specified areas, and resumed everyday duties. The crews lit cigarettes,

talked in low tones, and became acquainted trooper passengers. Pilots and

co-pilots made a last-minute check instruments and controls. Radio operators

examined their transmitters and receivers but they kept their hands off the

master switch. There was no test transmission. All that bad been done before.

At 2215 boars the perimeter track was bare of trucks. C-47's stood silently and broodingly on

their dispersed hard-standings, apparently deserted. Few knew that within their cavernous

interiors was the red glow of cautiously-smoked cigarettes and subdued

conversation Shot through a thread of high seriousness. The blue of the long

twilight deepened. At 2300, engines again shuttered to life, exhausts

belched preliminary puffs of smoke. The roar of engines grew to an

ear-splitting crescendo. Five minutes later aC-47 rolled down the runway with

navigation lights ablaze and ascending with its precious cargo. For thirty minutes aircraft took the

aircraft took the air. The squadron

contributed aircraft to the Group formation 47. Circling the field, their

amber lights added a thousand stars to an already star-filled sky. At 2349

hours, the Group Set course. One might night have thought that by this time the

well- kept secret would be “out-of-the-bag”.

True, this display of Troop Carrier might had

aroused some wonderment. About

midnight, an officer with several men of the intelligence section, visited

the mess hall for coffee. (There still many caffeine-crammed hours or work to

do that night.) The KP in charge of night coffee inquired, "Say,

Lieutenant, what's going on around here?

Aren't you fellows working a little late?" The check points of the flight plan contained many- a

dear name to Americans’ heart---Gallup, Flatbush, Atlanta, Paducah, Spokane,

etc. The wing rendezvous point, elko, was reached

at 0056 hours. The aircraft left the

coast of England, Flatbush, 0109 hours and pushed on across the Channel.

Pilots had expected a heavy barrage of flak at landfall on the French coast,

Peoria, so they were considerably cheered when, at 0154 hours, they found

this coast slumbering and peaceful. As they eased their heavy aircraft down

through scattered clouds at 1700 feet, the remained alert. They wondered when the 19 formations of